An early post on the blog put forward the idea that information, more than matter and energy, was responsible for the utility of objects. Recognizing the separation of information from these more traditional "stuff" delineators makes for new, and exciting opportunities for manufacturers. One of the fundamental tenets of Humblefacture is that complex order -- valuable information -- can be confered to matter without overly expensive machinery, or outrageous expenditure of energy. Moreover, because this order in the final object can at some point be described as information (a digital file, for example), this methodology of fabrication opens the door to global remix, re-purposing, and conversation, without the need to send heavy matter. This would fundamentally upset the current "developed vs developing" world structure -- designers everywhere would be able to make anything they had the wit to crystalize out of a single share idea ocean. While this might seem outrageous to product designers (I know I've gotten weird looks from my fellow IDSAers), practitioners of origami have been used to it for a while.

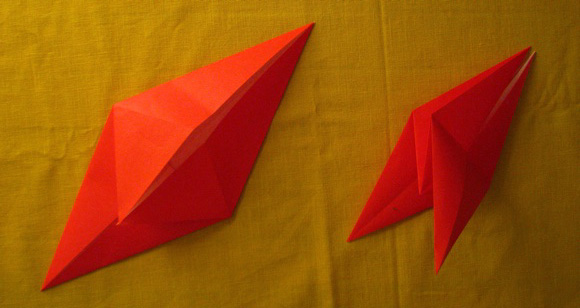

Origami is more or less the epitome of humblefacture (albeit with somewhat limited application). Essentially, every origami object is the same matter, informed with very different patterns, or layers of patterns. Most Origamists -- professional origami folders -- think of paper folding in this way. Imagine the simplest bit of information you can impart to a piece of paper - a single fold. This fold doesn't change the matter of the paper at all, just the relative orientation of that matter. A more complex pattern might be, to fold a piece of paper a few times, resulting in a useful set of pointy bits and flappy bits. This is called a base, because it serves as the basis upon which various more complicated models are built. Oriversity gives an overview of the commonly used origami bases here. The image below shows two simple bases, fish on the left, and bird on the right:

The fish base, made using 6 folds, results in a shape with two small pointy flaps (fins) and two large points (head and tail). Additional folding of a base takes the rough appendages and informs them further into shapes which more closely model the target animal. For example, the bird base can be made into a crane with a long neck with 4 additional folds, or a vulture with slightly more, different folds.

You could think of the base as being one pattern of folds, with another pattern (vulturization, for example) laid on top of it. But it gets even cooler. There are multiple levels at which these patterns exist -- patterns for adding eyes to heads for example, or making blobby feet into feet with toes. A frog like this one, with simplified feet establishes a basic skeleton of informational resolution. That same frog skeleton can be further complicated with a graft of additional information -- patterns for the feet to add toes.

This concept of pattern grafting has been taken to a ridiculous extreme by Robert Lang, probably the coolest origamist alive (in my opinion). This Koi fish model has no scales, but he also developed a model which uses the same pattern of the fish, but imposes a second global pattern of scales across the fish.

On the other end, Robert has written software (and pencil and paper methods) which allow you to calculate a novel base given a specific need for a certain number and size of legs in the final model:

What is exciting about these developments is that all the components are more-or-less modular, and remixable at a variety of scales. Using the technique that Robert developed to put the scales on the fish, you could literally put scales on an elephant -- indeed, somebody used the scale technique to inform this dragon's hide.

This modularity means that shared models are useful for something more than making the object they describe. Someone looking to do a salmon might take an earlier salmon model as a base, and add scales, or modify the fins or tail using a different pattern. Another benefit of this system is that nobody has to be an expert on everything. As with library-based software programming, people can draw on multiple experts from the field, and mix in their own expertise to create a novel recombination with novel features.

An overarching goal of Humblefacture is to develop methods and tools which allow more modular remixing of the information behind objects. If you've got any suggestions for existing solutions or new directions for this sort of development, I'd love to hear about them in the comments.

|

1 comments

]

1 comments

I'm dying to see the original Koi fish! I think the link is broken tho.

That's an interesting angle on open development. I'm intrigued by how these layers of complexity interface in origami - does adding three toes to a frog's foot mean additional folds way back at the start, or is it a case of sliding on a three toed 'sock' onto the simplified foot?!

Post a Comment